Between 1793 and 1798, the Spanish artist Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, Goya for short, was middle-aged, deaf, and weakened by serious illness. During that time, he produced what many regard as his most important work.

For Goya, his imagination came to life, as it were, during this period of failing health. As English essayist Joseph Addison put it, “suffering has a tendency to unlock the darker parts of the human mind.” Of course, it can also be said that it has the potential to unlock the lighter parts as well.

Goya’s drawings were heavily satirical and often dealt with vice, falsehood, superstition, and fear. The subjects: power-hungry politicians and clergy engaged in illicit activities, shrouded in the darkness of night.

While Goya was busy producing these drawings at the dawn of the 19th century, his concern for the human condition and his critique of the society of his time seem in lock-step with conditions in the 21st century that exist today.

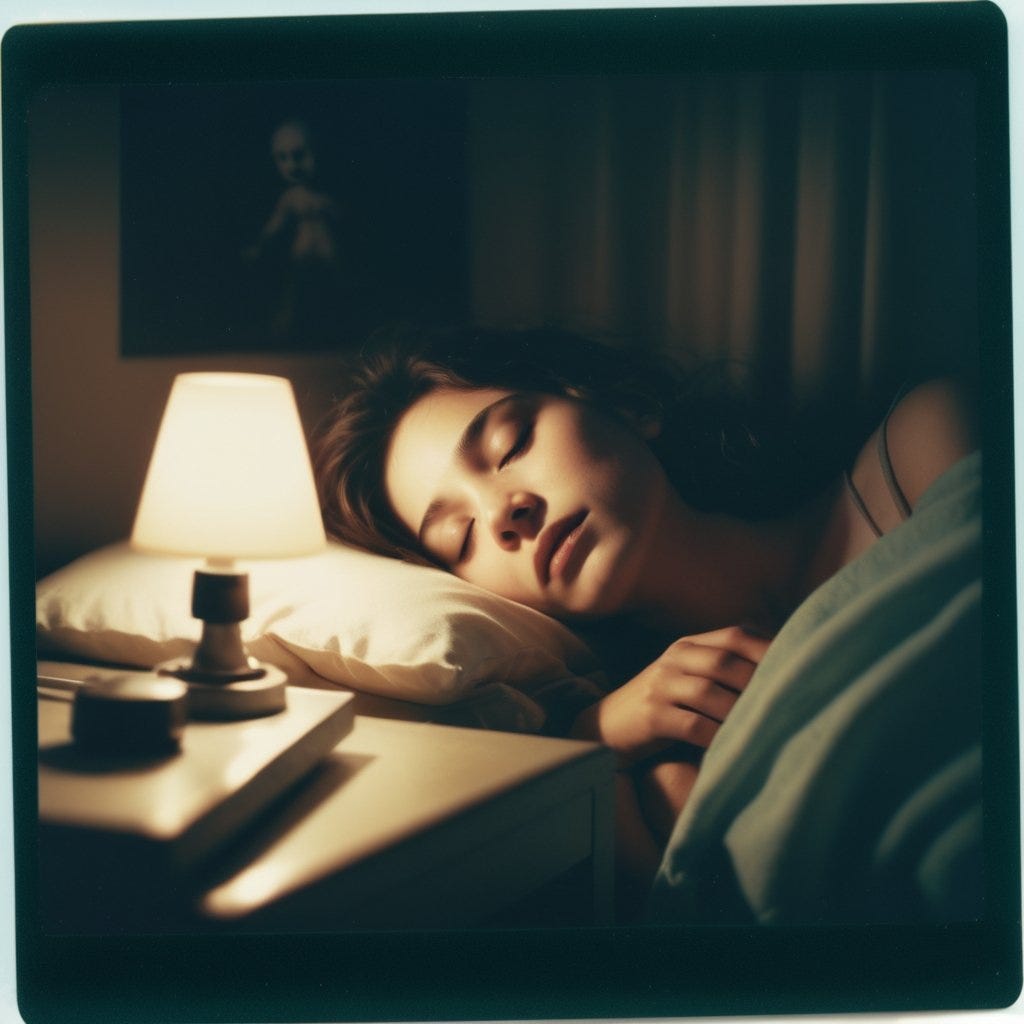

In one of his drawings, a man sleeps in a seated position with his head and arms resting on a platform. Bats and owls threaten from all sides, the most prominent of which stares out of the drawing at the viewer. The words, “el sueño de la razon produce monstruos” — The sleep of reason produces monsters — are written across the front of the platform.

History books refer to the period from 1685 until 1815 as the Age of Reason or Enlightenment. The collective of human knowledge exploded during this period.

Of course, the proliferation of new discoveries didn’t magically slow down in 1815. I’m writing this article using technology that couldn’t have been described in the language of 1815, and the creation of new technologies and new ways of understanding the world are increasing at such a pace that no single person can maintain a grasp on it.

It’s paradoxical, in a very real way, that the exponential advancement of technology has not been accompanied by a proportionate increase of any kind in individual or group critical thinking.

The stupidity that often accompanies group think is nothing new. As one of my favorite websites (despair.com) puts it, “Never underestimate the power of stupid people in large groups.”

Galileo, now regarded as the father of science, was repeatedly censured and confined to prison for large portions of his life by the Spanish Inquisition because of his “radical ideas.” The European precursor to the Salem Witch Trials resulted in more than 50,000 people being wrongfully executed because their views and practices didn’t align with the predominant religious practices of the region.

Fearmongering and bigotry have perhaps been around since the dawn of humanity. They may change clothes with each generation but the message is always the same: Be tolerant and accepting of others and their ideals, as long as they think like you and embrace your ideals.

Goya’s prescient commentary and the enduring nature of human folly make it clear that the basis of his critique remains relevant today, perhaps even more so than when he was alive. Our rapid technological advancements have created an illusion of progress, yet the fundamental flaws in our collective reasoning persist. Goya used his art to cast light on the absurdities and dangers of his time, and we have to recognize that our modern society, despite its advancements, is still susceptible to the same traps of fear, ignorance, intolerance, and avarice that existed more than 200 years ago.

Navigating in this complex world requires that we cultivate real open-mindedness. This means actively listening to, understanding, and appreciating different perspectives, rather than dismissing them or even railing against them.

It’s hard to recognize our own biases and even harder to work at overcoming them, fostering within ourselves and around us an environment where diverse ideas can be shared and debated with mutual respect and civility. That, I think, was the idea of the Enlightenment: to create a safely-guarded space against the metaphorical monsters that Goya warned us about — the dangers that arise when reason is abandoned.

To progress as individuals and societies, we have to be less judgmental and more willing to engage in civil discourse. Embracing reason and empathy will counteract the divisiveness and ignorance that undermine societies. Goya was right: the sleep of reason does produce monsters. Our vigilance, critical thinking, and compassion for each other will keep those monsters at bay.